Q Gathering 2010: Heralding the Arrival of Post-Christian America

American Christianity is beginning to look a whole lot different.

Picture hundreds of jeans-clad 20- and 30-somethings filling the floor of a vintage opera hall in Chicago, armed with laptops, smart phones, and iPads. Picture a stage backed by a large screen, dark but for a large white image in the center — not a cross, but an upper-case “Q.” Picture a guy with the shaggy blond bangs of an indie-rock guitarist taking the stage to launch the proceedings with the matter-of-fact acknowledgment that we have entered a new “post-Christian context.” Imagine three days of quick-hit presentations on everything from emotionally intelligent robots to nuclear weapons abolition, from fatherlessness to coffee-growing for the common good — and nary a word about abortion or “reclaiming America for Christ.”

If the arrival of the “post-Christian age” is upsetting to this emerging generation of (mostly) evangelicals, they did an awfully good job of hiding it at the recent “Q” gathering — the signature annual event for these next-generation Jesus followers. In fact, judging from the spirit and energy reverberating through the hall, I get the sense that they find the whole thing liberating.

“Christians can bemoan the end of Christian America,” shrugs Q creator and convener Gabe Lyons, “or we can be optimistic about it. What’s good is that it forces us to get back to the basics of serving people and loving our neighbors. Through history, Christianity has affected more people from that position than from a position of dominance.”

“Christians can bemoan the end of Christian America,” shrugs Q creator and convener Gabe Lyons, “or we can be optimistic about it. What’s good is that it forces us to get back to the basics of serving people and loving our neighbors. Through history, Christianity has affected more people from that position than from a position of dominance.”

If this is how it’s going to play out, the end of Christian America could turn out to be a profound blessing for American Christianity.

You can learn a lot about something from its name. Besides its edgy graphics and stage design, Q provokes surprise and curiosity with that name — a name that reveals volumes about these young- and mid-adulthood Christians and where they are coming from in their conceptions of the faith and its place in the culture.

As they keenly sense, a major problem with evangelical Christianity in our time has been its bold assertion that is has an answer — the answer — to everything, namely, a particular understanding of the Bible and how it applies to present-day issues. Not that they are any less on fire for Jesus, but these Q-generation Christians are comfortable in complexity and ambiguity. The new guard seems to be pleading with the elders: “It’s not that simple!”

Hence, the name “Q” and the ethos it suggests. Think of it an ongoing question-and-answer session–Q & A, but minus the “A.”

“Having the quick answer to everything doesn’t exhibit the humility that Christ exhibited,” Lyons explains. “We don’t want to project answers to questions that people aren’t even asking.”

Clearly, one of those questions-they-aren’t-asking (or not asking as much) is how to get to heaven. A major focus of conventional evangelicalism, eternal salvation gets less emphasis from the emerging generation. Addressing the hells on earth is what really interests the activists, church-planters, innovators, and social entrepreneurs who form this loose movement.

Between pauses for praise songs and worship, the Q conference buzzed with new possibilities for meeting human need and alleviating suffering around the planet. Among the projects and causes promoted by speakers in their three-, nine-, and 18-minute time slots: gospel-fueled drives for nuclear disarmament and protection of the environment, a shoe company that gives a free pair to a poor child for each pair sold, a plan to reform American education, and a coffee company that grows its beans in Rwandan fields where former enemies now work together. But don’t get the impression that this was a grand exercise in leaning left. One presentation, for example, made the case for delaying sex until marriage.

Fewer than a third of the participants at this year’s Q are 40 or older. More than half work in professions — or “channels,” in Q parlance — other than the church world, including business, arts, media, and education. One table included a brain surgeon from Kansas and the creator of a large organic farm in Idaho dedicated to feeding poor people. Appearing on stage were high-profile figures like CNN reporter Soledad O’Brien, who reflected on her recent experiences covering the disaster in Haiti, and Joshua Dubois, head of President Obama’s Office of Faith-Based and Neighborhood Partnerships.

In his new book To Change the World, religion professor James Davison Hunter uses the term “faithful presence” to describe his vision for a new kind of publicly applied Christianity. Hunter, a man in his fifties, is not a part of the Q generation. But he is clearly a sympathizer. He advances a model that that eschews political battles and aggressive promotion of doctrine. Hunter calls on Christians instead to use their lives and institutions as vessels to bring goodness and compassion into their social and professional spheres and the public square.

The 35-year-old Lyons has perhaps an even more compelling way to describe a role for Christians in pluralistic America — to be a “blessing” to society. A huge and necessary first step, he says, is for evangelicals to break free of the Christian subculture they constructed over the last century and engage with non-evangelicals. “We have a chance now,” Lyons says, “to show that following Jesus is not defined by heritage or politics, but by the church serving as countercultural example and as a curious, winsome presence in a broken world.”

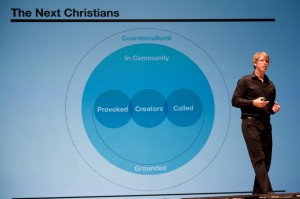

If anyone understands the attitudes of younger Americans on questions of faith and culture, it’s Lyons. A graduate of Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University, Lyons is the co-author, with David Kinnaman, of a highly influential book that used extensive public opinion research to explore and document public perceptions of Christianity. The title of the 2007 volume summed up the findings with a stark phrase: unChristian. Since then, Lyons has been on a mission to help steer Christianity in a direction that makes it more humble, hopeful, and attractive, a vision he describes in his forthcoming book The Next Christians: The Good News About the End of Christian America.

The Q cadre has its work cut out. Around the time of their late-April gathering, the news outside was menacing. The storylines about the Gulf of Mexico oil spill were changing from “problem” to “disaster.” Anger was boiling over the just-passed immigration law in Arizona. A would-be terrorist almost succeeded in wreaking carnage with a Times Square car bomb.

But in their presentations and intermittent table conservations, the young Christian idealists seemed undaunted. They plotted ways to use social media more effectively to collaborate on projects. They made commitments for serious action that they would take over the next year. They saw opportunities to take immediate action — and did. Such was the case with one foursome who, when asked for a few coins by an African-American homeless man on their way to a nearby sandwich shops, did him one better and invited him to dinner. What followed was 45 minutes of intense listening, prayer, and, at the urging of their homeless guest, a quick burst of gospel-singing on the street corner.

If this is what the end of Christian America looks like, it portends good things for Christianity. Not to mention the rest of that “post-Christian” society sharing space and time with these galvanized young Jesus followers.